NYS Conference of Local Mental Hygiene Directors, Inc. | An Affiliate of the New York State Association of Counties >

Hot Topics / Priority Issues

Substance Use Issues Are Worsening Alongside Access to Care

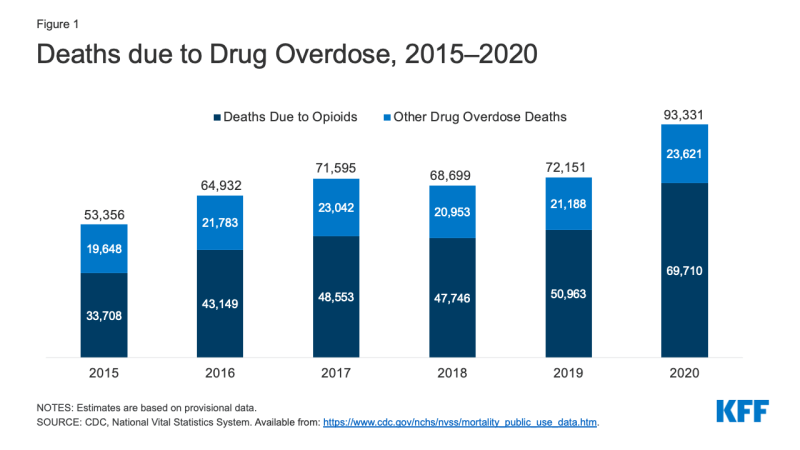

Amid the crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States is also facing a worsening substance use crisis. More than one in ten adults have reported starting or increasing the use of alcohol or drugs to cope with the pandemic. Additionally, deaths due to drug overdose spiked during the pandemic, primarily driven by opioids. Recently released data shows that over 93,000 drug overdose deaths were reported in 2020 – the highest on record and nearly a 30% increase from 2019 (Figure 1).

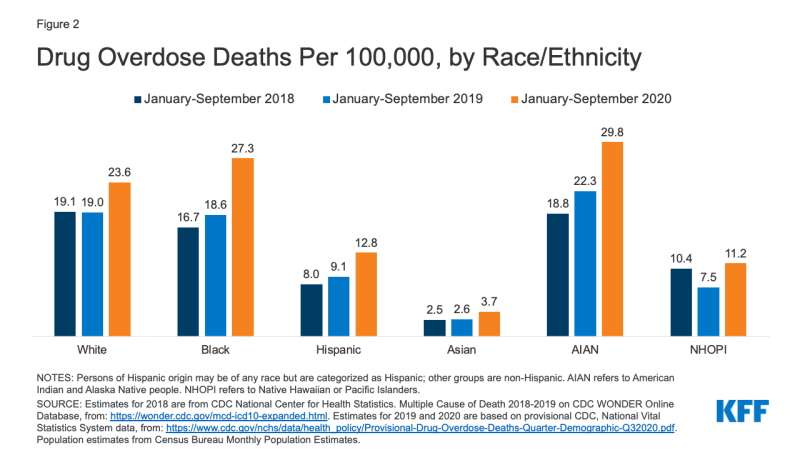

The recent uptick in substance use issues is disproportionately affecting many people of color. Between 2018 and 2020, drug overdose death rates increased across all racial and ethnic groups, but increases were larger for American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), Black, and Hispanic people compared to their White counterparts (Figure 2). Reflecting these increases, drug overdose death rates were highest for AIAN (29.8 per 100,000) people, followed by Black (27.3 per 100,000) and White (23.6 per 100,000) people as of 2020.

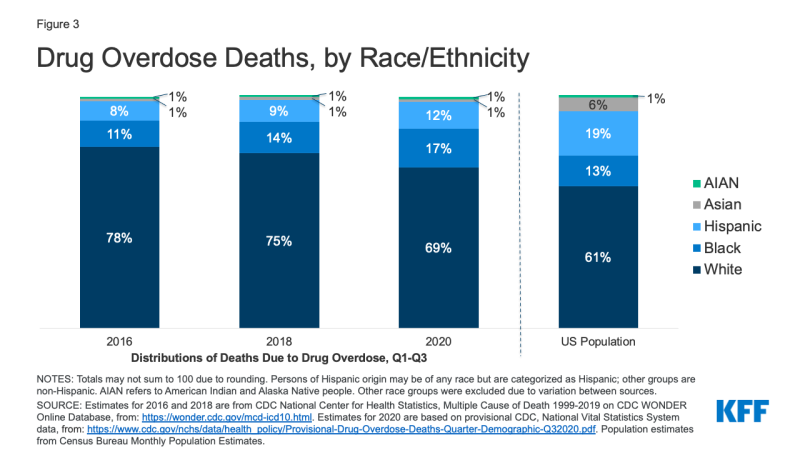

White people continue to account for the largest share of deaths due to drug overdose, but people of color are accounting for a growing share of drug overdose deaths over time. Between 2016 and 2020 the share of drug overdose deaths among White people fell from 78% to 69%, while at the same time the shares of deaths among Black and Hispanic people rose (from 11% to 17% and 8% to 12%, respectively) (Figure 3). As a result of this increase, Black people now account for a disproportionate share of drug overdose deaths relative to their share of the total population (17% vs. 13%). However, the share of drug overdose deaths among Hispanic people remains lower than their share of the population (12% vs. 19%). The share of deaths among White people remains higher than their share of the population (69% vs. 61%), although this difference has narrowed.

These recent trends are contributing to emerging disparities in drug overdose deaths among Black and AIAN people, which may worsen if they continue. Other recent data also suggests that people of color are disproportionately experiencing substances use problems. In a survey from September 2020, larger shares of Hispanic (28%) and Black (19%) adults reported starting or increasing the use of alcohol or drugs compared to White adults (13%) since the pandemic began. Additionally, fentanyl-related deaths, which have accounted for many drug overdose deaths during the pandemic, may also be disproportionately affecting Black communities. These increases in substance use problems come at a time when many people of color have faced a number of negative effects of the pandemic, including increased mental distress and job loss and infection and deaths due to COVID-19.

Substance use issues were a concern even before the pandemic, yet many of those in need of care, particularly people of color, were not receiving treatment. In 2019, over 20 million people over the age of 12 reported having a past year substance use disorder (SUD). However, only 10% of these individuals reported receiving care. For those individuals with a past year SUD and an unmet need for treatment, 24% reported not knowing where to seek services and 21% reported not having health insurance and being unable to afford the cost. Data from 2018 found that among those who began substance use treatment, the treatment completion rate was less than half (42%). These access to care issues and low utilization rates were more pronounced among people of color. Compared to White people, Black and Hispanic people had more limited access to buprenorphine and they were less likely to utilize specialty treatment and complete publicly-funded treatment programs. AIAN people also faced limited access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) services. Compared to other race and ethnicity groups, Asian people were less likely to receive needed substance use treatment; however, Asian and AIAN people had higher treatment completion rates.

There is some reporting and evidence indicating that access and utilization of substance use services has further worsened during the pandemic. Early on in the pandemic, there were reports of some state and local programs decreasing funding for substance use services, though these funds may be restored as state budgets bounce back. Other media reports have highlighted treatment centers limiting their patient capacity or facing difficulty with patient retention, while some centers have closed. A recent analysis found that in 2020, there was a drop in initiations for addiction treatment in California. Other research during the pandemic suggests that although buprenorphine prescriptions for existing patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) decreased in 2020, the decrease was generally offset by an increase in the quantity supplied with each prescription. Among new patients with OUD, however, buprenorphine prescriptions were low after the pandemic began and through August 2020 at retail pharmacies across the U.S. Similarly, in Pennsylvania, buprenorphine prescriptions remained low among new patients with OUD through October 2020. Research also suggests that fewer naloxone prescriptions were filled during the pandemic. Many syringe service programs, which also provide naloxone, have had to suspend or change the way they operate their programs.

There have been some recent policy actions to address the worsening substance use crisis. The American Rescue Plan Act allocated roughly $4 billion in funding for mental health and substance use programs, including $1.5 billion in block grants for substance abuse prevention and treatment and $30 million for overdose prevention and harm reduction programs. Several recently introduced bills include the LifeBOAT Act, which would attach a fee to opioid pain medications to be used toward substance use treatment; the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act 3.0, which would expand availability of medication-assisted treatment; and the STOP Fentanyl Act, which would improve public health surveillance and education and expand access to treatment. Some restrictions around delivery of substance use care have also been lifted; many clinicians are temporarily able to see patients via telehealth, and guidelines have been issued to increase access to buprenorphine in opioid use disorder treatment. Additionally, steps have been taken to expand access to and enrollment in health coverage in recent months. The Biden administration also released a statement on drug policy priorities, including greater access to evidence-based treatment and recovery support services, increasing harm reduction efforts, and addressing racial equity issues.

While policy measures may provide some relief to the substance use crisis, a number of challenges remain. Factors associated with substance use, including job loss and poor mental health outcomes, remain above pre-pandemic levels, and may further contribute to substance use problems. Longstanding stigma associated with substance use problems may also continue to affect access to care. These challenges underscore the importance for policymakers, providers, and researchers to consider how substance use issues will impact people even as the pandemic subsides.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.